Map-like representations of famous Buddhist monasteries form a unique and little-known genre of Tibetan painting in which architecture is the primary subject. These paintings illustrate real historical buildings, unlike paintings of Buddhist mandalas and celestial palaces, which are idealized, visualized spaces. As a result, architecture paintings do not adhere to the same structured iconographic and iconometric rules that apply to sacred images used for meditation and visualization practices. Instead, these paintings were used as pilgrimage maps and mementos of a pilgrim’s journey to a holy site. The portable format of the scroll paintings also meant that they could be rolled up and easily brought back to a pilgrim’s home as devotional objects that carried the aura of the holy place itself.

A Monastery Map

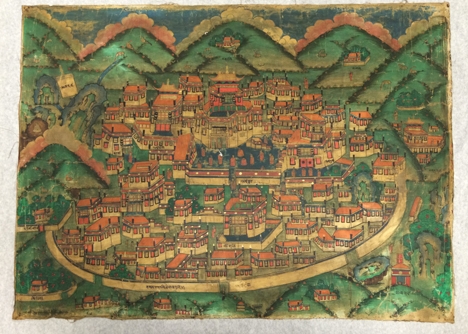

One example of this type of architecture painting is a previously unidentified monastery map that came into the Rubin Museum collection as a generous gift in 2006. The painting depicts Drepung Monastery (‘Bras spungs, ‘Rice Mound’), one of the three main monasteries (along with Ganden and Sera) near Lhasa in Tibet that are known as the ‘Three Great Seats of Learning’ (gDan sa gsum) of the powerful Gelukpa school of Tibetan Buddhism. Founded in 1416, Drepung Monastery became one of the major centers for advanced Buddhist training in central Tibet and asserted political and economic power from the mid-17th to the 20th century. Monks came from across Tibet, Mongolia, and the culturally Tibetan areas of northern India to pursue their Buddhist education at this prestigious institution. In its early years, Drepung was the residence of the Dalai Lamas prior to the construction of the grand Potala Palace in Lhasa under the Fifth Dalai Lama in the 17th century.

In this painting, the Drepung monastic compound is depicted in the manner of a holy Buddhist Pure Land, perched like a three-dimensional mandala atop a lush setting of rolling hills, flowers and animals, stylized rocks, and a schematic formation of cloud-topped mountains in the upper register.

Characteristic of Tibetan monastery paintings, this piece uses a high viewpoint that allows the viewer to look down onto the main buildings of the massive monastic city that was once residence to as many as 8,000 monks. At the center of the monastic compound is the main temple or tsuglagkhang (gtsug lag khang). This structure is characterized by a large, open-air courtyard facing a two-story assembly hall surmounted by a golden Chinese style roof. The monastic compound is divided into four colleges or monastic subunits called dratsang (grva tshang), which each had their own administration and community of monks in residence. These four dratsang are named Ngagpa, Loseling, Gomang, and Deyang. Another interesting feature of the monastery is the presence of reliquary stupas dedicated to the 2nd – 4th Dalai Lamas who once resided here, thus contributing to the sacred aura of the place.

As is the case in this image, it is common for Tibetan architecture paintings to feature identifying labels in Devanagari script that roughly corresponds to the Tibetan place names. It may indicate that they were painted by a Nepalese artist or made for use by Nepalese pilgrims in central Tibet. By contrast, a more stylized painting of Drepung Monastery held in the collection of the Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire / Koninklijke Musea voor Kunst en Geschiedenis in Belgium (Ver. 350, HAR 51646) has inscriptions in Tibetan and is thought to have been made by a pilgrim from the Amdo region of northeastern Tibet.

Sacred Visual Models

Pilgrimage paintings that depict the main monuments of central Tibet, such as the Rubin Museum’s ‘The Potala Palace and the Main Monuments of Lhasa,’ demonstrate the artists’ careful portrayal of the crucial architectural elements of each monastery. The strong similarities between many of these paintings suggest that they were widely transmitted across Asia and served as models for artists who could replicate the images of the sacred monasteries without ever seeing them firsthand.

Daily Life

The inclusion of vignettes of ritual processions, monks debating in the monastery courtyards, pilgrims along their journey, and other scenes of daily life adds to the charm of this genre of painting, as well as evidences the important functions of architecture in the social and cultural life of Tibet.

Add Your Thoughts

Comments are moderated, and will not appear on this site until the Rubin has approved them.