The spiritual and secular afterlives of bodies

Dead bodies create dilemmas. Whether or not you believe in a soul and its afterlife, we all—saints, secularists, and spiritual seekers alike—have to cope with corpses.

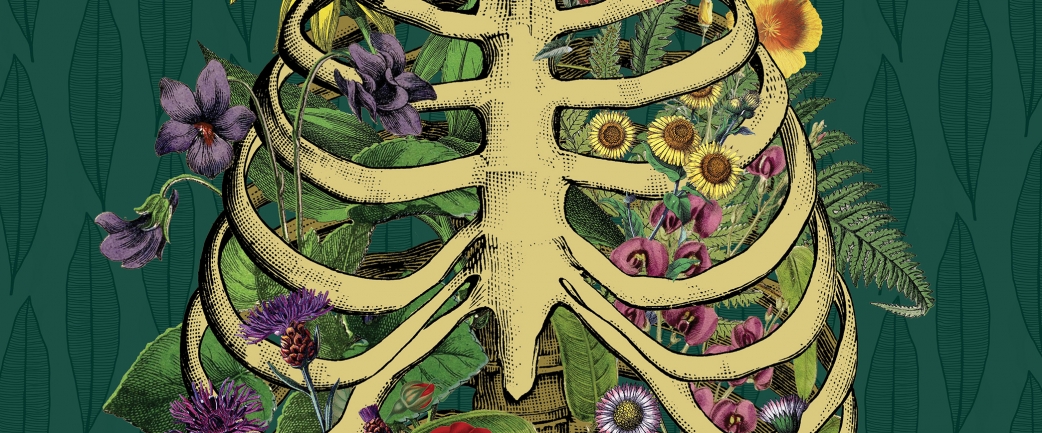

The body itself has its own afterlife, its own place in the world, and these days there is a staggering array of ways to take care of the dead body. As climate change has become a greater threat, many new funerary practices have turned to so-called green burials, environmentally sustainable modes of laying the dead to rest. Such burials enable people to have afterlives by returning their bodies into the cycle of nature in a gentler way than most modern methods have allowed.

There are biodegradable coffins available for the deceased, or bodies can be buried vertically, thus saving ground space. The departed can be interred in natural burial grounds, cemeteries where bodies are buried without coffins or environmentally damaging embalming fluids. Green headstones—trees, shrubs, or natural stones—can replace quarried granite grave markers.

In 2015, for the first time in the United States, there were more cremations than burials. Part of the reason is cost—it is cheaper to cremate than to embalm and bury—but cremations have also gained in popularity because of environmental concerns.

The Florida-based company Eternal Reefs goes one step further by taking the cremains—cremated remains—of an individual’s body and incorporating them into a special concrete mixture. The concrete is formed into ball-like structures that are placed in the ocean to aid in coral reef rebuilding projects.

Yet cremation itself has come under fire in the new wave of green burials, since cremation relies on natural gas to burn the body and emits pollutants into the atmosphere. A company called Resomation in Glasgow, Scotland, aims to address these issues. It offers a new form of cremation using a water and alkaline solution to dissolve the body. After the solution dries an ash-like residue is all that remains.

A company in Washington state is skipping the cremation step altogether and going straight to what is known as natural organic reduction, informally known as human composting. Based in Seattle, Recompose works on the basis of recomposition, converting human remains into soil. Founder Katrina Spade is working to launch a vertical burial facility that looks like an industrial tower but functions like a high-tech composting bin. It will move bodies through a series of stages until all that is left of the human is humus.

These emerging practices are all in keeping with current environmental concerns, but they are also about a contemporary, secular vision of the afterlife. They rest on a belief in the ongoing material and energetic nature of life here on Earth, with or without heavens and hells. Green burials have become a way of acknowledging that the environment has a sacred value that is to be treated with care and respect. They allow people to create meaningful rituals and invest in a heritage that lasts beyond one’s own life.

On its website, Eternal Reefs states its practices offer families “a permanent environmental living legacy,” while Resomation chose its company name from a Greek/Latin derivative meaning “rebirth of the human body.” In a CityLab interview about Recompose, Spade said she is interested in environmental issues and the ability to “create usable soil” that turns into “something that you can go grow a tree with and have sort of this ritual around that feels meaningful.” None of this is institutionally religious language, but it’s not far from it.

Caitlin Doughty calls herself a “progressive mortician,” and she is probably doing the most to revolutionize American attitudes toward the dead bodies of our loved ones. In books, TED talks, and blogs, she encourages people to not let the professional death industry take care of the deceased. She describes how families can care for the body themselves, in their own ways, on their own terms. Ritual is key in the process of death and grieving according to Doughty. It doesn’t matter what beliefs people hold, but it is important to perform symbolic, meaningful gatherings around the dead body.

Secular environmentalists are not the only ones following the green burial path. The Sisters of Loretto, a group of Catholic nuns in Kentucky, used to donate their bodies to science postmortem. Then they created the six-acre Nature Preserve Cemetery, which allows green burials. Because of the land’s changed legal status, it is now harder for companies to build industrial developments through eminent domain. This is essential, as a few years ago the Bluegrass Pipeline threatened the Kentucky environment, and the Sisters of Loretto joined with environmentalists to protest the invasive work.

Religious traditions themselves have long had what we would describe today as environmentally friendly funeral practices. In the sky burials of Tibet, bodies are left out to decompose and be fed upon by vultures. The simplicity of Muslim funerals calls for the dead body to be washed, wrapped in a simple cotton or linen shroud, and buried—as embalming is forbidden in the Islamic tradition.

How humans take care of their dead, and by extension how they value the body, offers clues as to what they hold sacred at any time, regardless of religious belief and unbelief. The soulless dead body carries power and presence. It commands respect and demands to be treated thoughtfully and carefully.

Burials are linked to hope, whether it is the ancient Egyptians wishing for good journeys through the underworld, Christians seeking a heavenly afterlife, or modern secularists aspiring for a more sustainable future for our environment.

About the Contributor

S. Brent Plate is a writer, editor, and professor of religious studies at Hamilton College. His essays have appeared in Salon, Los Angeles Review of Books, America, The Christian Century, and The Islamic Monthly, and his books include A History of Religion in 5½ Objects: Bringing the Spiritual to Its Senses and Blasphemy: Art that Offends. He is currently writing The Spiritual Life of Dolls.