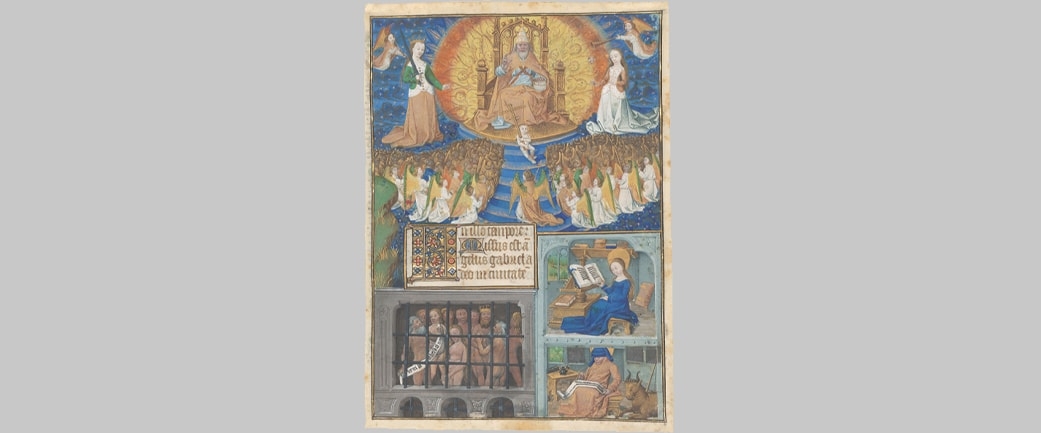

An unusual depiction of heaven reflects beliefs about life and death in medieval Europe

The paintings in illuminated manuscripts from medieval Europe offer fascinating insights into how life after death was imagined within the context of Christian beliefs. The Parliament of Heaven is one such richly illuminated leaf, or folio, with an unusual composition and meaning. It was originally part of a fifteenth-century book of hours, a devotional book used for prayer at fixed times throughout the day. The painting, on loan from the Morgan Library & Museum, is on display in the Rubin Museum’s cross-cultural exhibition Death Is Not the End.

Elena Pakhoutova: Why is this leaf titled The Parliament of Heaven?

Roger S. Wieck: It doesn’t refer to a biblical event. It’s based on legend and lore and arose in the Middle Ages as part of mystery plays, which often began with a scene called the parliament of heaven, with parliament meaning debate. Here God the Father is sitting at the top, flanked by two women who represent personifications of Mercy and Justice. They have debated whether God should give mankind a second chance for salvation. Because Adam and Eve committed sin, they and all of their children are forever stained and therefore are unworthy of heaven and salvation. Justice said, no, they had their chance. And Mercy said, it’s not fair to damn all of their descendants. God decides to come down in judgment in favor of Mercy. The cost of that second chance is the sacrifice of his own son, Jesus Christ. So the moment in time we see depicted is very specific and interesting. It’s the moment when God has made his decision to give humankind a second chance, but he yet has not yet dispatched the angel Gabriel down to earth to visit the Virgin Mary and tell her she will become the Mother of God—the Annunciation.

On the lower left, you see what looks like a dark prison with a lot of naked people inside. That’s a rare depiction of limbo—limbo before Christ’s time, which was filled with what the Christians called the Just Folk of the Old Testament, those who deserved heaven, but they couldn’t enter it yet because Christ had not yet come down to earth.

Can you say more about the depiction of heaven?

God the Father is surrounded by gold and red glowing colors that represent the cherubim and the seraphim. Those are the angels without bodies. What’s particularly notable about this depiction of heaven is that there are no humans there yet, because they haven’t been admitted.

Could you say that heaven is in waiting to receive those souls who are stuck in limbo?

Absolutely. After the crucifixion, when Christ died on the cross, he descended into hell, but that’s a bit of a misnomer because what he actually descended into was limbo. We see Christ tearing down the doors of that space and pulling the just out by hand; he usually reaches for Adam first as the first of humankind. These souls were then released from limbo and taken into heaven. Heaven then became populated with people.

I find it interesting how the depiction of heaven is relayed in the implementation of colors and little details, like these golden flecks that look like stars.

They are stars. And what comes off as kind of gray blobs are actually clouds, and it’s quite possible that those clouds were originally executed in silver. There is also an interesting green ground with grass on the far left, a suggestion of the earth. I think that has been put there as a kind of transition between the celestial paradise of heaven and the subterranean jail cell of limbo.

I understand that many people would be involved in the creation of a book of hours, from scribes to book binders. Who would decide to incorporate unusual depictions or iconography?

A book with this unusual kind of subject matter would have been requested by the patron of the manuscript. For a bespoke book like this they would have said, I don’t want the typical iconography. The typical iconography for this particular text is simply to have a picture of Luke sitting in his study writing. This patron wanted something different.

Would such lavishly produced books of hours be used on an everyday basis or only on special occasions?

The book of hours was popular from about 1250 to 1550, so about three hundred years, and it was mostly in the hands of laypeople. It was wealthy laypeople—royals but also wealthy merchants—who desired to have their own book for their own democratic access to God. And it was a book that ideally was prayed from every day throughout the course of the day.

This leaf dates to about 1465, and about twenty years later, in about 1485, Parisian presses started printing books of hours. So the price went down, and the books became accessible to a whole other class of people. One thing that made them appealing is that the patron buying the manuscript or even the printed book could have some influence over its textual and pictorial contents, so they could personalize it. It often became a family heirloom and was passed down from parent to child. Some manuscripts have, for instance, family records of marriages and births and deaths and such on their flyleaves.

Did the fact that they were made for lay people help to sustain this diversity of images?

Yes. And I should also note that books of hours were not controlled by the church. They were produced by lay professional scribes and illustrated by lay professional artists for a lay market, so you didn’t go to your parish priests and ask permission to have certain subjects in your book of hours. That was between you and the publisher. There’s great freedom there.

Did the depiction of heaven change in these books over time?

One of the most common depictions of heaven in books of hours come within depictions of the Last Judgment. Typically, Christ is sitting on a rainbow flanked by John the Baptist and the Virgin Mary, with the rising dead popping out of the earth towards his feet. On the left is Peter near a tower, welcoming the saved into the pearly gates of heaven, and on the right, the damned being cast into hell. That’s the more normal context of how heaven is depicted. The depiction on this leaf is already very different because of the presence only of angels and of no humans whatsoever. It makes it a different kind of heaven, almost like a pre-heaven in a way.

How did this folio enter your collection?

In 2015 a couple who are dealers sent me an email with the image, and I was quite struck by it because I immediately recognized that it was by an artist called the Master of Jacques de Luxembourg. The Morgan has have a great book of hours by the Master of Jacques de Luxembourg, which I remembered was missing some miniatures. So I could tell from the leaf, from its subject matter and the text, that it was the beginning of the gospel lesson according to Luke.

When I went to our manuscript, which is M.1003, I indeed discovered that the beginning of the gospel lesson for Luke was missing from our manuscript. And from the number of lines and from the kind of decoration that was on the back of the leaf, I could determine that indeed the leaf that they had sent me was not only by the Master of Jacques de Luxembourg but was actually from our M.1003.

Through the provenance research that I did, I found out that the leaf had been sold in Germany in 1930, and then it reappeared in Switzerland at auction in 1965. That instantly raised a red flag in my eyes, because there is a great hole in the Nazi years. So sadly, we declined obtaining the leaf. Then two years later the dealer Jörn Günther sent me an email with a picture of it. Jörn and his team were able to plug the provenance hole. They found out through contacting dealers with their records and annotated sale catalogs that there was a man or a person named Trier who bought the item in 1930, and the person who sold it in Switzerland in 1965 was also named Trier. So it was either the same man or the same family, but in any case, there was no longer a hole in the provenance. A combination of a gift of funds from Margaret Steed Hoffman and a grant from the Bernard H. Breslauer Foundation enabled us to purchase this leaf.

Do you know the provenance of the M.1003 book of hours in your collection?

The book of hours has a longer provenance and it includes the Robert Hoe collection. His catalog was published in 1909, and through it we know that there were four miniatures missing when he owned it. So the four miniatures went astray before 1909. The manuscript itself was given to us in 1979 as a gift from Mr. and Mrs. Landon K. Thorne, Jr. When we got the manuscript, we already knew that it had four miniatures missing. The other three miniatures can be accounted in the following way: One is in the the Musée de Picardie in Amiens, France. There is another in a private collection in New York, the Trinity, and that is a promised to gift to us. Then there is a missing Flight into Egypt, and the traces of that have disappeared.

See The Parliament of Heaven and other representations of the afterlife, from both Christian and Buddhist traditions, in the exhibition Death Is Not the End at the Rubin Museum from March 17, 2023– January 14, 2024.

About the Contributors

Roger S. Wieck is the Melvin R. Seiden Curator and Department Head of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York, where he oversees more than eleven hundred manuscripts, spanning some ten centuries of Western illumination. Previously, he held curatorial positions at the Walters Art Museum and the Houghton Library of Harvard University. Wieck has written numerous books including The Medieval Calendar: Locating Time in the Middle Ages (2017).

Elena Pakhoutova is a senior curator of Himalayan art at the Rubin Museum of Art and holds a PhD in Asian art history from the University of Virginia. She has curated several exhibitions at the Rubin, most recently Death Is Not the End (2023), The Second Buddha: Master of Time (2018), and The Power of Intention: Reinventing the (Prayer) Wheel (2019).

Image Credit

Master of Jacques de Luxembourg (French, active 1465–1470); Parliament of Heaven; Eastern France or Paris; ca. 1465; 1 leaf: vellum, illuminated, matted; 8 3/4 x 7/16 in. (22.2 x 16.4 cm); The Morgan Library & Museum, New York; Purchased on a grant provided by the Bernard H. Breslauer Foundation and with a gift from Marguerite Steed Hoffman, member of the Visiting Committee to the Department of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, 2017; MS M.1207