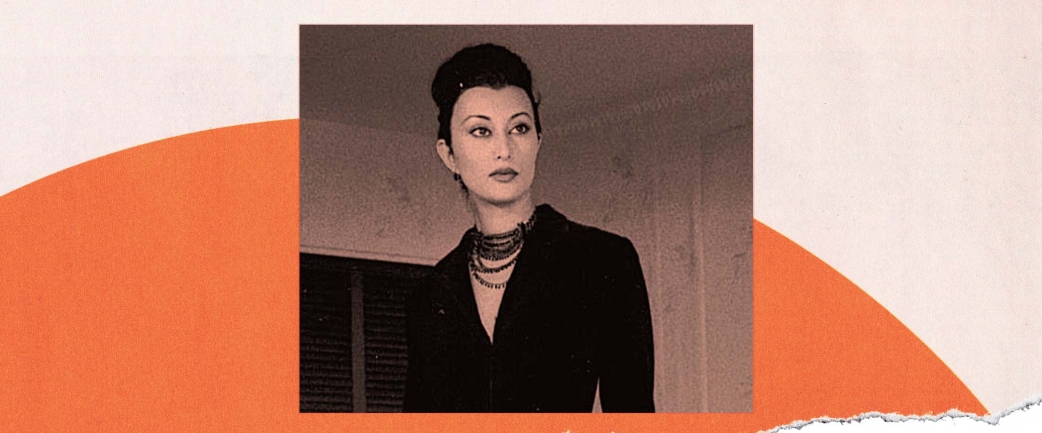

Aria Drolma left her career as a fashion model, embarked on a traditional Buddhist three-year and three-month silent retreat, took the vows of an ordained Buddhist nun, and learned how to live in the present moment.

Howard Kaplan: Was there a difference in how you perceived time before and after you entered the retreat?

Lama Aria Drolma: Yes, a big difference. While living in New York City, the value of time is material, and you often hear the phrase “time is money.” Likewise during the three-year retreat, time was very important, but in a different way. We contemplated “Time and Impermanence,” one of the four Buddhist thoughts that turn the mind to dharma. It teaches that everything in this world is impermanent. The next breath may be our last. I began to understand every moment in reference to impermanence.

Did the time pass differently during each of the three years?

The first year felt very slow. The second year was a little faster than the first, and the last year zipped by! When I came out of the retreat, I wished that it had lasted one more year.

How did you mark time during the retreat?

In the retreat we followed time by the sounds of a gong or a bell. I did not wear a watch and there was one very precise clock. Each month one of us was the timekeeper. We rang a bell for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, while every practice began with a gong. The first meditation began at 4:00 a.m. I had an alarm, but I always woke up a minute or two before it rang. I developed an internal clock that I had lost when I lived in New York City. I think that’s true for many people. We don’t depend on our internal abilities; we tend to look outward instead.

What emotions are associated with time, specifically in terms of the future?

Before the retreat, when I thought of the future, the unknown was quite daunting, and yet at the same time, it was exciting since the canvas was so huge to create whatever I desired. By nature I’m a very positive person. I was confident I could set any goal and achieve it. But there came a time when I felt I was at life’s crossroads—my spiritual seeking was overpowering. Everything that seemed exciting became overwhelmingly meaningless and senseless. My life goals that had at one point been all consuming seemed uninteresting and unimportant. I was seeking answers for my life’s purpose. I was searching for more meaning in life.

When did you begin your meditation practice?

The year 2008 was a time of soul searching. I found a Tibetan Buddhist meditation center in New York City, and I was determined to make positive changes in my life. My exciting lifestyle and fashion career were becoming more and more meaningless and senseless. I made a firm New Year’s resolution to start to meditate again and to enrich my life spiritually. Through the practice I began to see how our thoughts create the suffering in our day-to-day lives based on hope and fear—hope for the future and the fear that we may not attain our dreams. During meditation I learned to observe my thoughts and to not follow the past thoughts, since the past is gone, and to not follow the thoughts of the future, since it’s not here yet, but to rest in the present moment.

EXCLUSIVE CONTENT

Has spirituality always been a part of your life?

When I was around eight-years old, my father left the family to become a renunciate, a sadhu. This planted a seed in my mind for my own spiritual awakening. Whenever I saw a holy man wandering the streets, I would look to see if it was my father. As was the custom in India, we always offered food for the holy men, and I would make sure we always had a plate ready in case my father returned home. The pivotal point in my spiritual awakening was when my mother passed away. The pain of losing my mother was intolerable after losing my father as a child. I learned the most meaningful lesson of impermanence: I realized that life is short and nothing lasts forever.

Could you speak at all during the retreat?

Our day began at 4:00 a.m. and ended at 9:50 p.m. For most of the day we were silent. We were allowed a short period of time after lunch when we could speak. Inside the retreat it was mostly silent, but we could communicate with notes if needed.

Did you have access to the outside world?

There were no newspapers, computers, or internet, and no phones were allowed. We could write two letters each week and receive letters and parcels each Friday. We were allowed to send four letters a month to friends and family, but if we needed we could write more letters. Receiving and writing a letter was a big distraction, so I kept it to the minimum. We were not allowed to step out of the boundaries of the two retreat houses (drupkang), one for men and one for women. We had a small courtyard we could walk around if we had time in the afternoon. If there was a medical emergency, we could of course leave for treatment.

Did you ever miss your previous life?

Even when I was modeling and working in advertising, I felt that there was one side of me that was into the glamour world, while the other side was very spiritual. Although I enjoyed the creative side and all the beauty and glamour, I noticed how shallow my former world really is. I began to recognize the illusion of it all. When I was working in advertising, I noticed that our creative team would Photoshop the images of even the most beautiful model who was chosen for a catalogue’s cover. I realized that even she was not perfect and not really who she was portrayed to be. What were we saying to the young people who wanted to be like the model on the cover? What we were portraying was a total illusion.

What is the significance of the length of the retreat—three years, three months, and three days?

The reason is explained in Jamgon Kongtrul’s Retreat Manual. Briefly, according to the Buddhist Kalachakra, or Wheel of Time, “The most fundamental relationship with the outside world after birth is through the breath.” The manual tells us that there are 21,600 minutes in one year, which corresponds to the number of breaths we take each day. A small percentage of each breath—1/32—is considered “wisdom energy.” According to Tantric Buddhism, our bodies can last one hundred years. If you do a little math, you’ll see that the wisdom energy accumulated over that time is equivalent to the span of three years, three months, and three days. That becomes the ideal length of time for the retreat and the time required to change karmic energy into wisdom energy.

About the Contributors

Lama Aria Drolma was born in India and has taught at the Hindu Samaj Temple & Indian Cultural Center & Jain Temple and the Chapel for Sacred Mirrors in Poughkeepsie, New York, as well as the Rubin Museum of Art, Tibet House, Harvard Business School Women’s Association, and the United Nations in New York City. She also volunteers for several nonprofit organizations and has worked as a fundraiser for breast cancer and HIV-AIDS related issues.

Howard Kaplan is the former editor in chief of Asiatica, the annual magazine of the Freer and Sackler Galleries, Smithsonian Institution. For his writing he has received fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and the Edward Albee Foundation among others. He currently divides his time between New York and Washington, DC.