Tantric ritual technologies involving mantras, charms, paintings, and sculptures enabled rulers to conquer enemies and harness power.

“Non-humans who conceal [themselves] by magical emanation, of such high and low

[places] as Jang (Lijiang) of the [Mongol] empire which comprises everything under the

sun, listen [to my command]!

It is absolutely forbidden to harm those who hold my [decree] by such means as the

harmful eight classes of gods and demons, curses, invocation rituals to destroy enemies,

malevolent spirits, poltergeists, and oath-breakers. [All] must heed this decree by Ga

Anyen Dampa!

However, if there are those who disobey, [I vow by] the Three Jewels that, having

unleashed the fierce punishment of the Dharma Protectors, their heads will split into

one hundred pieces!”

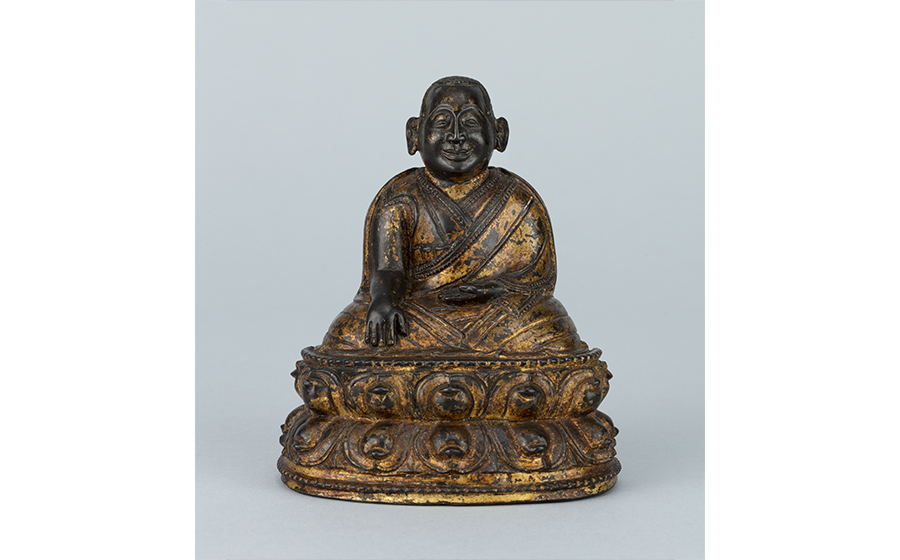

So reads a decree by Dampa, a thirteenth-century ritual specialist of the wrathful deity Mahakala at Qubilai Khan’s court. The decree, which doubles as a protective charm for those who carry it, demonstrates Dampa’s willingness to mix political authority with tantric power, the human realm with the spirit world.

The force of religion to claim political power is the focus of the exhibition and publication Faith and Empire: Art and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism offered Inner Asian empires a symbolic path to legitimation as well as a literal means to achieving physical power: a ritual technology that we would characterize today as magic.

The image of a monk meditating in a remote cave is a Western romantic stereotype that limits our understanding of the wide range of Tibetan religious activity. In reality, many religious figures have played much more active, engaged roles in history, acting as court chaplains who served their ruler-patron’s needs. Monk-rulers also rose to power, conflating the interests of religion and the state. For the imperial courts of Asia, one of the great appeals of Esoteric Buddhism was its claim of efficacy in dealing with worldly goals and the military application of its rituals that reflected a zeitgeist of subjugation, coercion, and control—in a word, power. Rulers and imperial courts were less interested in meditation or enlightenment and more concerned with what religion could do for the state: protecting the nation; extending the life, wealth, and power of its rulers; curing epidemics; controlling the weather; and pacifying or killing its enemies

Tibetans embraced the tantric developments of Buddhism in India, such as the recasting of the Buddha as a nexus of spiritual and political authority, which eroded the distinction between secular and sacred power. With this merging of sacred and worldly imagery came the elevation of wrathful deities to the status of buddhas. These deities and their practices were not just useful in terms of overcoming obstacles to liberation but also in accomplishing more mundane worldly ends. The second chapter of the Hevajra Tantra, for instance, includes detailed descriptions of rituals to destroy an enemy army and even their gods.

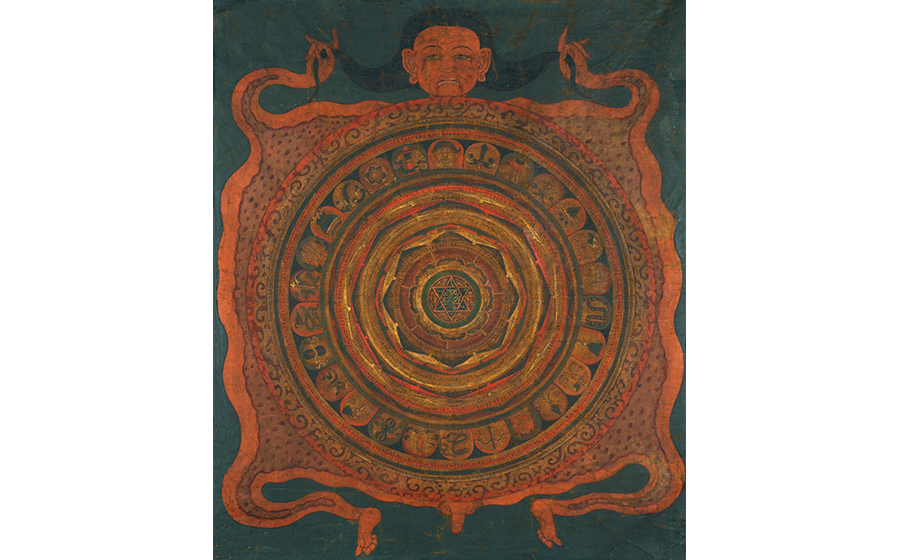

As scholar Bryan Cuevas explains in his chapter on magical warfare in the Faith and Empire catalog, tantric ritual was seen as a potent technology to control both the internal and external worlds, with four main goals: pacification, enrichment, subjugation, and destruction. Tibetans viewed the legendary eighth-century wizard Padmasambhava—who is said to have engaged in magical battles with local gods and demons to tame the region—as a source of the most potent forms of such magical power. A wide array of images, such as human effigies like this painted version or more abstract ritual dough-offering sculptures (torma), were employed to both ward off danger and subdue or destroy one’s enemies.

Magical warfare, and the charisma of those who mastered it, became an important part of political legitimacy in the Tibetan Buddhist world. Lama Zhang is a fascinating study in the political and martial employment of Tantric Buddhism in the twelfth century. He engaged in political and military affairs, ruled territory, and enforced secular law. He even sent his own students into battle as part of their religious practice. In addition to conventional weapons, Lama Zhang employed a ritualized warfare of magic spells, purportedly aided by powerful protector deities such as Shri Devi and Mahakala.

Tibetan Buddhists, known for the efficacy of their ritual magic, also served imperial courts to the east, such as the Tangut kingdom of Xixia (1038–1227). One cleric associated with the Tangut imperial line, Tsami Lotsawa, is linked to at least sixteen texts on the wrathful deity Mahakala, including The Instructions of Shri Mahakala: The Usurpation of Government, a short “how-to” work on overthrowing a state and taking power. When Chinggis Khan first laid siege to the Tangut capital in 1210, the Tangut’s Tibetan court chaplain summoned Mahakala to the battlefield, at which point the dams the Mongols were using to flood the city burst, drowning Mongol troops and forcing Chinggis to withdraw. Tibetan accounts clearly state that when the imperial preceptor made a torma he had a vision of Mahakala on the battlefield, and the Mongols were forced to retreat. This account of their unusual military setback through effective religious ritual no doubt caught Mongol attention.

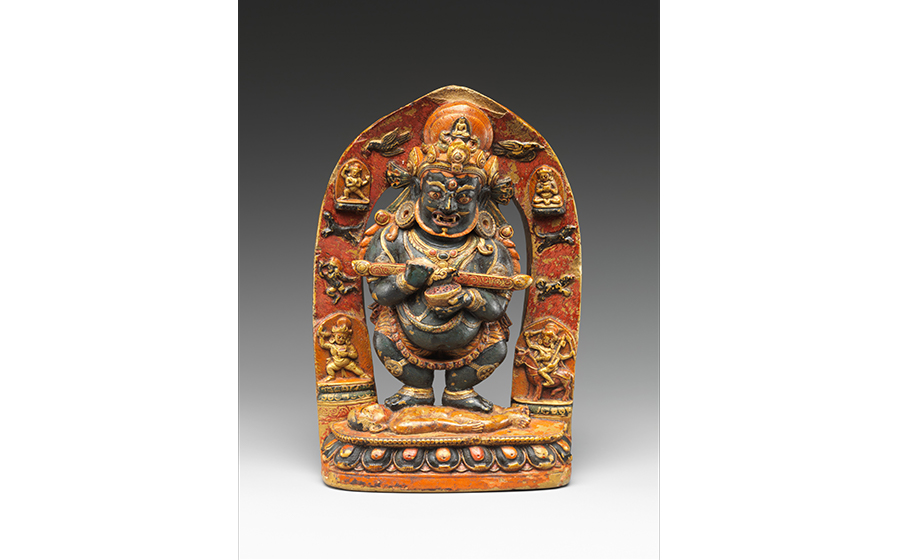

The Mongols adopted the Tangut practice of employing Tibetans as their preceptors, and the wrathful deity Mahakala became the state protector and focus of the imperial cult. Mahakala (“The Great Black One”) was credited with intervening in several key battles. For instance, early in the Mongolian campaign to push south in China, Qubilai Khan’s ritual specialist at court, the aforementioned Dampa, summoned Mahakala, who was seen going house to house on the battlefield. When the Chinese petitioned their god of war Zhenwu to deliver them, the Chinese god left a note on his altar saying that he had to yield to the Black God leading the Mongol army.

In the most famous example, Qubilai Khan asked his Tibetan preceptor for Mahakala to intervene against the Southern Song, which his greatest general could not conquer. A temple was erected with its image facing south, and shortly thereafter, the Song capital surrendered. When the former Song emperor and his courtiers were brought north, they were astonished to see the image of Mahakala just as they had seen him among Mongol troops. This sculpture used in the conquest of China became a potent symbol of both Qubilai Khan’s rule and the Yuan imperial lineage.

Not all Tibetans welcomed Mongolian involvement in Tibetan affairs, and repeated incursions into Tibetan lands resulted in a cottage industry of ritual war-magic specialists known as Mongol-repellers (Sokdokpa). For instance, the seventeenth-century Rikdzin Chodrak, the last figure in the lineage of this painting, was famous as an artist and for his magical repulsion rituals against Mongol armies. The deity Yamari, in the form of “Blazing Razor of Extreme Repelling,” is depicted in the center as a three-bladed ritual dagger used for pinning down malevolent forces and slaying demons, a form closely associated with the archetypal wizard, Padmasambhava.

By the seventeenth century, magic was an integral part of warfare and political legitimacy. Both sides used it in a protracted civil war in Central Tibet that brought the Dalai Lamas to power. The Fifth Dalai Lama’s arsenal of destructive rites included the fearsome deities Vajrabhairava, Yama Dharmaraja, and Shri Devi as Makzor Gyelmo (“Queen Who Repels Armies”). He recognized that the political charisma accrued to those who mastered such magical abilities was crucial to his regime’s survival.

The Mongolian helmet is a striking example of the deployment of magic on the battlefield. The interlocking letters of the Kalachakra mantra, known as “The Ten Syllables of Power,” are the central iconographic feature over the brow. Above looms the wrathful deity Vajrabhairava, one of the principle deities in the Gelukpa Order’s arsenal of destructive magical practices.

The emperors of the Manchu Qing dynasty (1644–1911) adopted Tibetan Buddhism as a means of political legitimacy and used war magic as one means to establish their authority. In the eighteenth century, the Qianlong Emperor, who positioned himself as an emanation of the Bodhisattva of Wisdom Manjushri, had a strong affinity with Manjushri’s wrathful emanation Vajrabhairava. Qianlong’s state chaplain Changkya Rolpai Dorje also intervened in battles on behalf of the Qing state. Rituals performed in the capital are said to have resulted in flames falling on the battlefield in Gyelrong (Jinchuan), one of the most costly, protracted wars of the Qing.

This aspect of the Tibetan tradition might come as a surprise—and even run counter to popular perceptions of Buddhism—but the employment of ritual magic was integral to the power of Tibetan Buddhism in politics. In a tradition where religion and politics were inseparably intertwined, it was only natural that rulers sought religious answers to tackle real-world problems, be it extending their lifespan or overcoming adversaries.

See these artworks and learn more in the exhibition Faith and Empire: Art and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism at the Rubin Museum, on view February 1–July 15, 2019.

Further Reading

Cuevas, Bryan J. “The Politics of Magical Warfare.” In Faith and Empire: Art, Politics and Tibetan Buddhism, edited by Karl Debreczeny, 170–89. New York: Rubin Museum of Art, 2019.

Dalton, Jacob. The Taming of the Demons: Violence and Liberation in Tibetan Buddhism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Gentry, James Duncan. “Representations of Efficacy: The Ritual Expulsion of Mongol Armies in the Consolidation and Expansion of the Tsang (Gtsang) Dynasty.” In Tibetan Ritual, edited by José Ignacio Cabezón, 131–63. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Goble, Geoffrey. “The Politics of Esoteric Buddhism: Amoghavajra and the Tang State.” In Esoteric Buddhism in Mediaeval Maritime Asia; Networks of Masters, Texts, Icons, edited by Andrea Acri, 123–39. Singapore: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak Institute, 2016.

FitzHerbert, S. George. “Rituals as War Propaganda in the Establishment of the Ganden Phodrang State.” In “The Ganden Phodrang Army and Buddhism,” edited by Alice Travers and Federica Venturi, special issue, Cahiers d’Extrême-Asie (forthcoming).

Sinclair, Iain. “War Magic and Just War in Indian Tantric Buddhism.” In War Magic: Religion, Sorcery and Performance, edited by D. S. Farrer, 149–64. New York: Berghahn Books, 2014

Yamamoto, Carl. Vision and Violence: Lama Zhang and the Politics of Charisma in Twelfth-Century Tibet. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

About the Contributor

Karl Debreczeny is Senior Curator of Collections and Research at the Rubin Museum of Art. His research focuses on artistic, religious, and political exchanges between the Tibetan and Chinese traditions. His publications include The Black Hat Eccentric: Artistic Visions of the Tenth Karmapa (2012) and the coedited The Tenth Karmapa and Tibet’s Turbulent Seventeenth Century (2016).